For decades, the autistic experience of attention has been described almost exclusively from an external, neurotypical perspective. The language used has often been rooted in a deficit model, with terms like “narrow,” “rigid,” “restricted,” or “obsessive” used to characterize the deep and passionate focus that is a hallmark of the autistic mind. But what if this entire framework is looking at the phenomenon through the wrong lens? What if, instead of a disorder of attention, it is simply a different, and in many ways more efficient, strategy of attention?

Enter the theory of Monotropism.

Developed in the 1990s by autistic researchers Dr. Dinah Murray and Wenn Lawson, monotropism offers a powerful and affirming “insider’s view” of the autistic cognitive style. It posits that the human mind has a limited amount of attention available at any given time, and that people deploy this attention differently. Monotropism theory suggests that the autistic mind tends to concentrate its attention and energy much more powerfully on a limited number of interests or tasks at once, creating a deep and intense channel of focus.

This isn’t a flaw. It is a fundamental difference in processing that explains not just “special interests,” but also sensory experiences, executive functioning, and the profound joy of the autistic “flow state.”

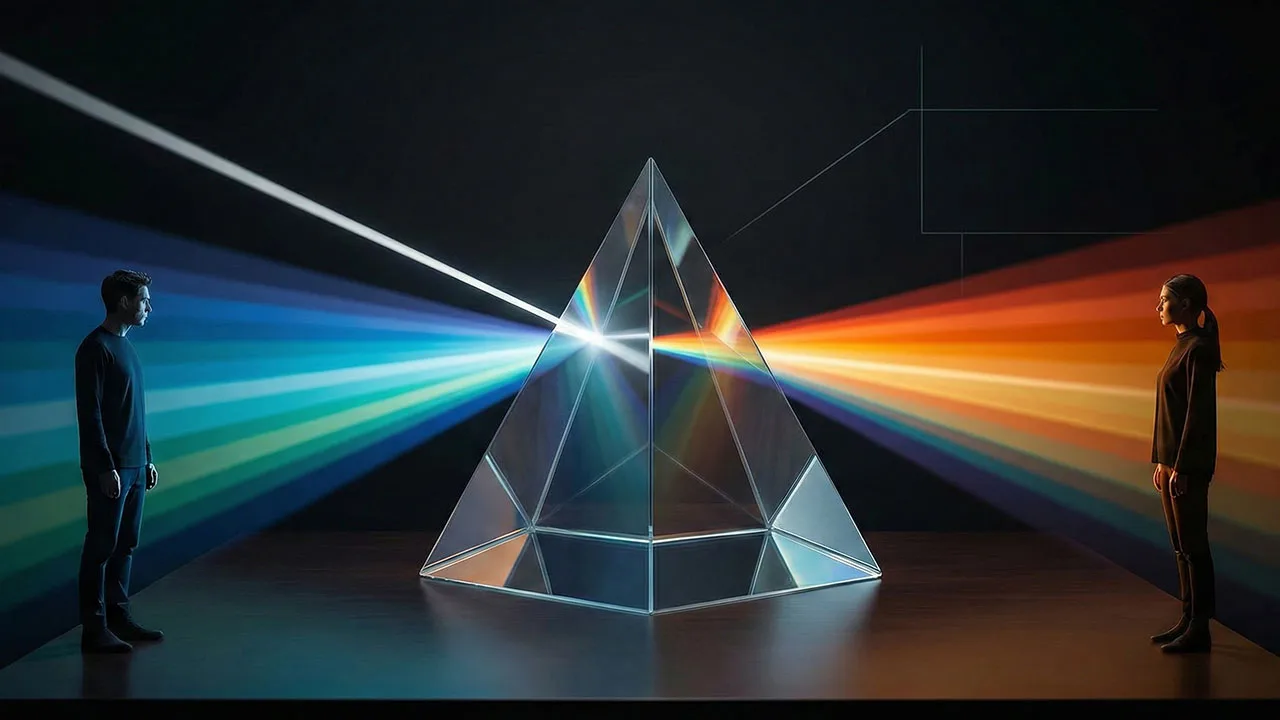

The Spotlight vs. The Floodlight: Monotropic and Polytropic Minds

To grasp the concept of monotropism, it is useful to contrast it with its counterpart: polytropism.

A polytropic mind, which is more typical of non-autistic individuals, is configured to process a wide array of information and stimuli simultaneously. It can track multiple conversations at a party, monitor various streams of sensory input, and switch between different tasks with relative ease. Its attention is spread broadly, like a floodlight illuminating a wide area with diffuse light. This allows for flexible social navigation and multitasking but often comes at the cost of depth.

A monotropic mind, in contrast, channels its available attention much more narrowly and deeply. Think of it like a powerful spotlight. It illuminates a smaller area, but with an intense, concentrated beam of light that reveals incredible detail. When an autistic person’s interest is captured, their attention gravitates toward it, pulling processing resources from other areas to create a highly focused “attention tunnel.”

This explains why an autistic person might be able to focus for eight uninterrupted hours on coding, cataloging a collection, or learning everything about a historical event, yet find it incredibly difficult to manage the “simple” task of getting ready to leave the house, which requires juggling multiple small, unrelated tasks at once.

The Experience of a Monotropic “Flow State”

When a monotropic individual is engaged in an activity that falls within their attention tunnel—what is often called a “special interest” or “passion”—the experience can be one of profound flow, joy, and well-being. This is far more than a simple hobby; it is a state of being that is essential for regulation and happiness.

- Intense, Effortless Focus: The outside world seems to fade away. Distractions, background noise, and even internal bodily cues like hunger, thirst, or the need to use the restroom can go completely unnoticed. This is often described as “hyperfocus.”

- Deep Engagement and Learning: In this state, there is a profound sense of immersion and connection with the activity. Information is absorbed rapidly and retained with incredible detail. This is the cognitive engine that drives the deep expertise and encyclopedic knowledge often associated with autistic passions.

- Intrinsic Joy and Regulation: Engaging with these interests is not done for external reward; it is intrinsically motivating and deeply fulfilling. For many autistic people, this flow state is a primary way to recharge their social and emotional batteries, regulate their nervous system after a period of stress, and experience pure, unadulterated joy. It is a fundamental aspect of autistic self-care.

The Challenges of a Monotropic Mind in a Polytropic World

While being monotropic is a powerful and valid way of processing the world, it presents significant challenges when navigating a society that is largely designed by and for polytropic minds. The friction between these two processing styles is often the root cause of what is externally labeled as “autistic deficits.”

- Difficulty with Task-Switching: Being pulled out of a monotropic flow state unexpectedly can be jarring, disorienting, and even physically uncomfortable. It’s not a simple matter of shifting focus; it’s like derailing a high-speed train. This explains why transitions can be so difficult and why an autistic person might not respond immediately when their name is called—they aren’t being rude; their cognitive resources are simply fully allocated elsewhere.

- Executive Function Strain: The demands of modern life—juggling emails, managing household chores, remembering appointments, and navigating social plans—are inherently polytropic. For a monotropic mind, managing these multiple streams of information requires an immense amount of conscious effort and energy, as it forces the brain to operate outside its natural, single-focus style. This constant strain is a primary contributor to autistic burnout.

- The Concept of Autistic Inertia: Monotropism also helps explain the phenomenon of autistic inertia. This is not just the difficulty in starting a task (procrastination), but also the difficulty in stopping a task once engaged. Both require overcoming the powerful gravity of the current state of the attention tunnel.

- Sensory and Social Overwhelm: In a monotropic state, the brain is filtering out a massive amount of extraneous information. In a busy, unpredictable environment like a crowded mall or a party, the brain is forced into a polytropic mode it is not optimized for. It becomes overwhelmed by the sheer volume of sensory and social data it is trying to process, leading to sensory overload and a rapid depletion of energy.

Why Understanding Monotropism is a Game-Changer

Monotropism is more than just an interesting theory; it is a revolutionary and affirming paradigm shift. It reframes core autistic traits from a perspective of difference, not deficit.

- It explains that special interests are not “restrictive obsessions” but are the natural, joyful, and necessary expression of a monotropic mind. They are a source of expertise, pleasure, and regulation.

- It clarifies why routines and predictability are so vital for autistic well-being. Routines reduce the cognitive load of having to constantly and effortfully shift attention between unexpected tasks, freeing up mental resources.

- It provides a compassionate lens for understanding social differences. An autistic person might miss some social cues not because they lack empathy, but because their attention is deeply focused on another part of the interaction.

By embracing the theory of monotropism, we can move away from trying to force autistic individuals to become more polytropic—a strategy that leads to masking and burnout. Instead, we can focus on creating environments, accommodations, and strategies that honor this deep, focused, and passionate way of thinking. It allows us to see the autistic mind not for what it supposedly lacks, but for the incredible depth, integrity, and passion it possesses.